Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome – a classic presentation

A 25-years old primigravida presented for obstetric ultrasound at 19 weeks of gestation. There was no significant personal or family history.

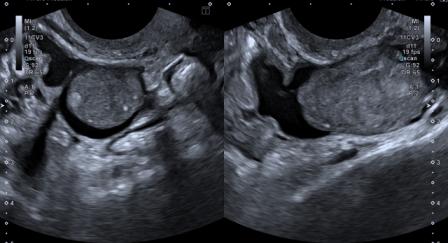

The ultrasound findings were as follows –

Figure 1: Absent nasal bone.

Figure 2: Soft-tissue hypertrophy of the right thigh and buttock. Cystic spaces are noted in the soft tissue.

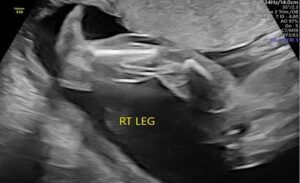

Figure 3: Soft-tissue hypertrophy of right leg.

Rest of the fetal anatomy was normal. No other abnormality was seen. Based on the findings, a diagnosis of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) was made.

The patient opted for medical termination of pregnancy. The following findings were noted after termination –

Figure 4a: Right lower limb soft-tissue hypertrophy with bluish discoloration due to cutaneous capillary malformation, confirming the diagnosis of KTS.

Figure 4b: Right lower limb soft-tissue hypertrophy with bluish discoloration due to cutaneous capillary malformation, confirming the diagnosis of KTS.

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), sometimes referred to as Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, is an angio-osteo-hypertrophic condition. Actually, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and Park Weber (PW) syndrome are two distinct entities but often clubbed together.

KTS is diagnosed when at least 2 of these 3 conditions are present –

1. Cutaneous capillary malformations

2. Bony or soft-tissue hypertrophy of an extremity (localized gigantism)

3. Varicose veins of unusual distribution.

The classic PW syndrome is characterized by presence of vascular malformation predominated by arteriovenous shunting and localized bony or soft tissue hypertrophy.

Most patients of KTS have all three features mentioned above. Involvement is mostly unilateral (85%).[1] Nearly 100% patients have haemangiomata and leg is the commonest site involved.[1] Most cases are sporadic and both genders are equally affected.[1]

Proposed pathogenic mechanisms for KTS are a mesodermal abnormality, abnormal regulation or growth factors primarily affecting angiogenesis.[2] Researchers believe that KTS belongs to PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum.

First prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of KTS was reported in 1988. The earliest prenatal diagnosis has been reported at 15 weeks, but most cases are diagnosed in second half of pregnancy.[1]

Other than asymmetric limb growth, other prenatal features include non-immune hydrops, polyhydramnios, cataract, cardiac failure, macrocrania, ventriculomegaly and hepatomegaly.[2] Vascular malformations of gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract may be associated.[3] Hand and foot defects have also been reported with KTS.[1]

Differential diagnosis includes Proteus syndrome, Beckwith Wiedemann syndrome, neurofibromatosis, soft tissue sarcoma and lymphangioma.[2]

In most cases of KTS, the prognosis is favorable after birth since hemangiomas tend to reduce in size.[1] However, large and extensive hemangiomas increase the chances of bleeding in post-natal period due to consumptive coagulopathy.[3]

© Copyright Reserved

References:

1. Ivanitskaya O, Andreeva E, Odegova N. Prenatal diagnosis of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: Series of four cases and review of the literature. Ultrasound (Leeds, England). 2020 May;28(2):91-102. DOI: 10.1177/1742271×19880327. PMID: 32528545; PMCID: PMC7254946.

2. Cakiroglu Y, Doğer E, Yildirim Kopuk S, Dogan Y, Calıskan E, Yucesoy G. Sonographic identification of klippel-trenaunay-weber syndrome. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:595476. doi: 10.1155/2013/595476. Epub 2013 Dec 3. PMID: 24368952; PMCID: PMC3866887.

3. Kharat AT, Bhargava R, Bakshi V, Goyal A. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: A case report with radiological review. Med J DY Patil Univ 2016;9:522-6.